Ben Sasse fears for our youth.

He is a U.S. Senator, and therefore he is a very busy man with little time to spare for side projects. Yet, so great is his concern for our kids’ predicament that he has taken the time to write a book about it. It is not a bad book, even if you disagree with what it says. You will have to trust me (or not) on the exact contents, because, “You may not make this e-book public in any way”, is all I will quote directly from it.

His thesis is laid out in the book’s title, The Vanishing American Adult, and he has summarized the gist of his prescription in the subtitle, Our Coming-of-Age Crisis – and How to Rebuild a Culture of Self-Reliance.

In the text, he depicts a generation afflicted by aimlessness. They have been stunted by coming up in the shade of social media and cultural relativism. Deprived of the harsh choices and bright lessons that come with social responsibilities and traditional rites of passage, kids have grown passive. They lack the ‘grit’ to sustain our society.

I won’t quibble with his depiction. Social media is a blight. The current generation operates on the assumption that ‘someone will take care of it’. Giving up is always an option for them.

I do disagree with his diagnosis and prescription, however. He seems to think that helplessness and hollowness result from a deficiency of citizenship. The correction would then involve a big shot of citizenship. He is completely mistaken. In fact, emptiness is the natural outcome of citizenship, and helplessness is just a reactive symptom.

On the most basic level, citizenship is a position in which one gets told that one’s life is fungible. One’s time, attention, motivation, and psyche can be chopped up and traded for goods to satisfy certain needs. Of course, Sasse recognizes this situation. He mentions “development of the individual” on a couple of occasions as a worthy pursuit, but only if it is pursued to certain ends (becoming responsible, self-sacrificing, ‘gritty’ – in other words, all those things that make a solid citizen). As far as I can tell, only the ends distinguish healthy developmental activities from selfishness, in Sasse’s estimation. And in a shocking coincidence, healthy ends are those for which the goods of citizenship come in handy.

“Why won’t my blood sugar go down?”

Maybe my analysis is unfair. Sasse contends that we are all a little defective, and our institutions may be a little defective, too. We should not expect a perfect synergy between man and social machine, even though the basic program is sound and actually the best that we can do.

But I hear differently all the time.

“I’m doing all those things that the diabetic educator told me to. I have changed my diet. I am walking every day. I am taking my medications like clockwork. So why is my blood sugar still high?”

This person is in my office every day, wearing a different, outfit, a different ethnicity, or a different gender. Yet they are the same person. They have a sit-down job, or two, in which they spend 40-60 hours per week dealing with an incestuous dataset – something so about itself, whether it is driving a cab or processing claims, that it demands attention to automatisms rather than any particular skill. To ensure that their attention does not waver, an overseer tracks their activities and rates their efficiency. Their extraneous physiological and psychological functions are regulated by the employer as distractions.

The citizen in my office sleeps 6 hours per night, or less. They drink energy drinks to keep going, and eat foods which the package or the vendor says are healthy, because they haven’t the time or energy to prepare their own food. They are too exhausted to exercise properly.

As a result, they are obese, diabetic and hypertensive. As a result, they now require one of the goods for which they can sub-divide themselves: medical care.

Which brings us to where the defense of citizenship as a natural-born fertilizer for human development, breaks down. The trouble with the whole thing is not the palate of goods on offer, their costs, or the means of valuation. The trouble is the chopping, because the roots of experience (attention, motivation, responsiveness, etc.) can’t be cut up for a purpose, especially for delayed gratification of a specific need. The very notion mistakes the nature of needs and the relationship between our needs and our activities. Here, Sasse may have been better served by spending a little more time reading Nietzsche, and a little less time reading Rousseau and the Bible.

For an organism’s needs can’t really be parsed. The motivations underlying our activities are merely aspects of a single motive which Nietzsche labeled ‘will to power’. Even when we try to perform an isolated act of attention, we feel something about it, our neuro-hormonal system responds to it, and it tires us globally.

But Sasse seems to think there’s a neat way around the problem of dividing the indivisible.

Life on the Farm or 8 Pitches Up?

In the latter half of the book, Sasse talks about how he sent his daughter to work on a ranch. The idea was to teach her how to enjoy work – not any particular task, but work itself. Basically, he sought to teach her how to thrive as an instrument. It’s pretty clever, really.

He explains the strategy in a vignette:

Martin Luther met a man who had just become a Christian and wanted to know how best to serve the Lord. He asked Luther, “How can I be a good servant? What should I do?” He expected Luther to tell him that he should quit his job and become a minister, monk, or missionary.

Luther replied with a question, “What do you do now?

“I’m cobbler. I make shoes”, the man answered.

“Then make great shoes”, Luther replied, “and sell them at a fair price – to the glory of God.”

In other words, find integrity in being a good instrument. I think the flaw in this reasoning is obvious: Why not make great shoes to the glory of Satan? It’s the devotion part that really matters, right? This notion of the human lost at heart and essentially in search of a set of rails (any rails) undergirds fascism through the ages, and it works superficially, so long as the social venue is stable.

But I took another path with my kids, because I learned more from sitting on a ledge, than I ever did from a job.

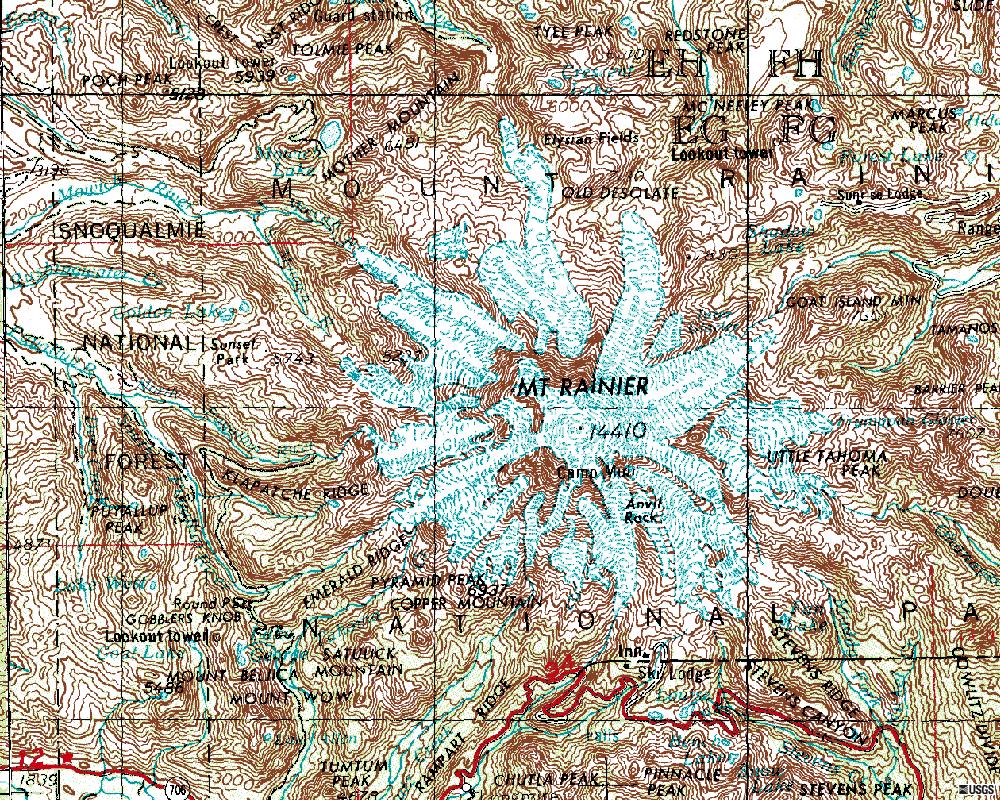

We have climbed several long routes together. We have looked up, down, and out from ledges in the middle of those routes and soaked in the lessons: however precarious the position, what falls to us is to pass the water around, check the system, and find our way through the next rope-length of terrain; trust your partners as you trust yourself; no matter how cold, hot, tired or thirsty you are, the beauty of the sky and landscape remain; achievement, i.e. ‘ticking the route’, doesn’t really matter – it is only a means to get you to the ledge.

In taking them on those climbs, my hope was to offer them a way of life which put making a living in perspective, rather than telling them that making a living would put everything in perspective for them.

A different vignette illustrates my point:

Cook Ding was cutting up an ox for Lord Wenhui. At every touch of his hand, every heave of his shoulder, every move of his feet, every thrust of his knee — zip, zoop! He slithered the knife along with a zing, and all was in perfect rhythm, as though he were performing the Dance of the Mulberry Grove or keeping time to the Jingshou Music.

“Ah, this is marvelous!” said Lord Wenhui. “Imagine skill reaching such heights!”

Cook Ding laid down his knife and replied, “What I care about is the Way [“Dao”], which goes beyond skill. When I first began cutting up oxen, all I could see was the ox itself. After three years I no longer saw the whole ox. And now, now I go at it by spirit and don’t look with my eyes. Perception and understanding have come to a stop and spirit moves where it wants. I go along with the natural makeup, strike in the big hollows, guide the knife through the big openings, and follow things as they are. So I never touch the smallest ligament or tendon, much less a main joint.”

“A good cook changes his knife once a year — because he cuts. A mediocre cook changes his knife once a month — because he hacks. I’ve had this knife of mine for nineteen years and I’ve cut up thousands of oxen with it, and yet the blade is as good as though it had just come from the grindstone. There are spaces between the joints, and the blade of the knife has really no thickness. If you insert what has no thickness into such spaces, then there’s plenty of room — more than enough for the blade to play about it. That’s why after nineteen years the blade of my knife is still as good as when it first came from the grindstone.”

“However, whenever I come to a complicated place, I size up the difficulties, tell myself to watch out and be careful, keep my eyes on what I’m doing, work very slowly, and move the knife with the greatest subtlety, until — flop! the whole thing comes apart like a clod of earth crumbling to the ground. I stand there holding the knife and look all around me, completely satisfied and reluctant to move on, and then I wipe off the knife and put it away.”

“Excellent!” said Lord Wenhui. “I have heard the words of Cook Ding and learned how to nurture life!”

— Zhuangzi, chapter 3 (Watson translation)

I do not see the current generation as sissified hedonists, any more than previous generations. The hypersensitivity, the passivity, the absorption (self and otherwise) all look like symptoms of a bunker mentality. They see what’s in store for them and they don’t like it, but they don’t seem to know how to resist.

A Sasse-type message has gotten through. The citizenry coming of age does think that it must learn to embrace a social role (little worker, little voter, little contributor) wholeheartedly in order to fully mature, and it just can’t bring itself to do so. The instinct is right. Kids growing up in this era are being asked to pursue a sort of faux-maturity which involves merely “giving up childish things”, and the achievement of that state will leave them empty and utterly dependent on a structure which deals with them on the basis of a flawed methodology.

They need a little less Ben Sasse, and a little more Cook Ding, when it comes to advice about how to grow up. Because maturity means dealing with your situation – not just endorsing it – and dealing with it artfully. It means getting over being The Cobbler, The Christian, The Cobbler-Christian, or even The Cook.

In Sasse’s terms, I have laid out the Romantic counter-argument to his Realist argument regarding the nature of the individual’s relationship to civilization. But I reject that characterization to some extent. There isn’t an inherent conflict between the individual and the civilization. We are stuck with our civilization. It lies before us like the carcass of a great ox, and it is just as indifferent.

We get chopped up in our interaction with it, but our own hand is on the knife. And I agree with Ben Sasse here, maturity is the solution. Not the faux maturity which the senator espouses, which is just a form of selling out, but actual maturity which sets limits and carves its own way, not towards some magical future, but like the cook’s knife, in the present where we all reside.