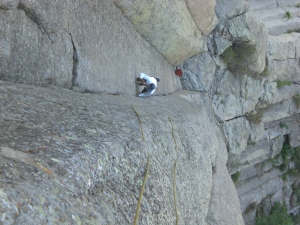

The Cathedral Spires after the beetles

The mountain pine beetle is a native son of the Black Hills, but nobody around here is very proud of the little guy. I like him. He’s tiny and a weak flyer. A victim of his own reproductive tactics, he’s a bit like the Lemming – doomed to population booms and busts that make him look stupid. Nevertheless, this little insect has thwarted the will of the baddest mammal on the planet.

For the most part, the life cycle of the pine beetle is typical, boring high school biology. It’s one of those egg-larvae-adult-egg affairs that fits well in a circle of arrows on the textbook’s margin. In late summer, adult beetles emerge from trees infested the year before and fly to new trees, where they burrow into the bark and lay eggs. The eggs hatch quickly into grub-like larvae which begin to eat the tender, inner layers of the bark. After a Winter’s break, the larvae finish their meal, metamorphose into adults and the cycle begins again.Within this staid tale, there are a few interesting details that, under the right conditions, conspire to make the smoldering, little endemic population of beetles into a conflagration.

First, there’s that Winter dormancy. To prepare for the cold, the larvae produce antifreeze. If cold weather strikes before they are ready, many will die. If they are ready, though, they can survive temperatures down to thirty below zero, Fahrenheit. Besides allowing more larvae to survive, adequate preparation means the larvae are further along in their development when they wake up in the Spring. Sometimes, they are far enough along to complete two generations in one year.

Second, the trees don’t just stand there and take it. They have an immune response to the beetles. As the insects dig into the inner bark, the injury prompts the tree to force resin upwards. Sap spills out of the defect in the bark, smothering the beetles. If the beetles are few enough, and the tree is strong enough, the immune system can prevail. In turn, the beetles have adapted to overcome the trees’ defenses. They produce a pheromone which calls other beetles to a tree under attack, giving them the opportunity to exhaust the tree’s immunity with sheer numbers.

Blue stain fungus

The beetles have also developed a symbiotic relationship with a fungus that weakens the trees. The ‘blue stain’ fungus thrives in the core wood of pine trees, where it interferes with water transport to the crown. Beetles carry fungal spores on their bodies as they breach the outer layers of bark which normally bar the fungus entry.

Under usual conditions, things work out so a few trees die and a few beetles survive. However, if the weather is right and the trees are already weak, a positive feedback loop ensues and the beetle population explodes. Usually these excursions amount to little bursts, limited by the availability of suitable trees. But presently, due to a lucky convergence of human and beetle preferences, there is no limit to the availability of suitable trees.

The forest that we have cultivated is made of trees which are just the species and size that the beetles prefer. Plus, we’ve made a dense forest, so even the mountain pine beetles’ weak flying skills carry them easily from trunk to trunk. Our relationship with the pine forest has unwittingly, coincidentally helped turn the little pops in beetle numbers into a boom. Modern human activity on the land, from fire suppression to agriculture to habitation, has attenuated a kind of herd immunity inherent in the age, size and density of the trees.

Cuttin’ & Chunkin’

Now, we are trying to stand in for that herd immunity. We want our forest back the way it was. It gave us logs, shelter and aesthetic satisfaction. So, we try to cut infected trees before the beetles can emerge. We try to trick the beetles with pheromones (the insects actually release a repellant pheromone when their host tree harbors too many beetles). We even spray neurotoxins on the trees in ‘high value’ areas, like Mt. Rushmore.

Beetle-thinned forest

Close up, our efforts look pretty smart, like a beetle attack on an individual tree looks smart, with its chemical communications, antifreeze equipped larvae, and fungal force multiplier. But just as the beetles are already doomed to population collapse by the time they start to thrive, we have already ensured that we won’t have the forest back the way we like it, simply because we liked it that way so much in the first place.

It will work out in the end. Preservation is a fool’s errand anyway. We pursue it for sentimentality’s sake, and because it makes us feel like we may be able to avoid our own eventual extinction. When the beetle epidemic is over, we will learn to like the new forest and maybe we will recognize the beetle battle as a farce. For at a proper distance, our interaction with the habitat is indistinguishable from that of the beetles. Like them, and the Lemmings, we’re condemned to a lifestyle that allows us to survive in spite of a built-in vulnerability to chaos.