Climbing is generally misunderstood. The sport’s diversity alone makes it opaque. The motivations of mountaineers, sport climbers, boulderers, alpinists and aid climbers are inherently heterogeneous solely based on the nature of the climbing discipline each group pursues. Add to that inherent diversity the large number of dilettantes and duffers which climbing attracts; participants who themselves do not appreciate all the possible benefits and dangers the sport offers. Little wonder the public sees climbing as a sort of gray soup with a troubling aroma, which would be a puzzling thing to sample voluntarily.

Among the various disciplines in climbing, soloing is the hardest to understand. Abandoning all safety equipment save one’s own body and adjunctive tools may appear foolish, bold, transcendent, or egotistical depending on the observer. It is a challenging taste for climbers and non-climbers alike.

To be clear, soloing means intentionally trying something hard without a rope, not accidentally venturing into a climb or die situation. Everyone has one or two of those in their closet. Nor does it mean dispensing with protection on ground one dominates. Purposefully entering a situation in doubt with the understanding that there will be no salvation takes something different and gives something different than those incidental circumstances. Much, perhaps most, of the climbing community disavows it. But the truth is, most who participate in the sport have pursued it at some point. That’s logical, since soloing is the only reproducible means of achieving one of the unique benefits of climbing: self-destruction.

We all harbor the urge. Who hasn’t felt the fleeting impulse to steer into a bridge abutment or fought the pull of the abyss while looking over the edge of a precipice? This impulse to rebel against the rules of self-control is quite reasonable. After all, our identity is just a convention. It is a yoke imposed by the thin layer of cells covering our brains on all the structures beneath. To have any hope of success, the self must be founded on a tyrannical belief in its own preciousness, only then does it have the strength to make the rest submit to the restrictions inherent in its own preservation.

This product of the cortex is illusory. Ever since we became aware, we have tried to wipe away the limits which the illusion imposes. Our religious history is a chronicle of such efforts and their failures. We have a messiah who cried out for himself from the cross. We have scores of Bodhisattvas, but no more Buddhas. Rather than unshackling us from our identity, religion has settled for turning the self against its own weaknesses, but the project of making us “good” has always been play-acting. Our consistent hypocrisy shows what a poor compromise it’s been. We were fools to think we could shake our identities in the presence of others. The only place to remove the self is in isolation, where it has no hope of salvation from outside.

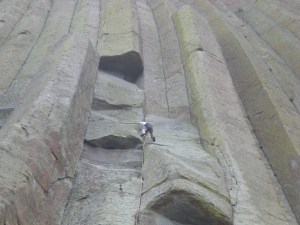

I have done a few solo climbs, but most were on the soft side. They were climbs I had done before with a rope or technically in little doubt. A couple have been for real, though, and the Black Ice Couloir was the realest of those. The route is not particularly hard from a technical standpoint. However, it is an alpine climb with attendant difficulties, including loose rock and variable ice conditions. At the time I climbed it, it was only a couple of grades below what I had ever climbed in the mountains and I was equipped with straight shaft tools, plastic boots and Foot Fang crampons. I wasn’t set to dominate the terrain.

I hiked up Valhalla Canyon the afternoon before the climb and tucked myself under a rock for the night. Several times on the walk up, I changed my mind. Immobility, nightfall and the confines of the bivy sack did nothing to ease the turmoil. Through the night I picked away at my fears with my ambition until both were in tatters. At about 2 AM, there was nothing left but the decision to climb. I sat quiet for two more hours, waiting for the alarm.

I moved up the first icefield by headlamp, and climbed a short, steep chimney on the right side of the headwall. A section of easy climbing passed quickly and I arrived at the second icefield with the light of day. Up to that point, I had felt calm, almost empty, but as I moved onto the ramp above the icefield, an intense focus and motivation took hold. Every move was perfect. A bolt of lightning couldn’t strike me from the rock. The traverse across the third icefield and the climb up the final gully seemed to pass in no time. The short mixed section where the ice ended felt so secure I wished it could go on forever.

Back in the sun, I made my way down to the lower saddle, lay down on the tundra and went to sleep. When I woke, I set off down Garnet Canyon and on to a path of destruction in the world beyond. I tried to bring that sense of perfection and unitary movement with me, to recreate it in the populated world. Of course, it stayed in the mountains, but the expectation was a portable hazard. A hard object, it battered everything softer than itself.

People and their things cannot reproduce the rewards of soloing, despite humans’ capacity to have those experiences for themselves. The preparatory tear-down itself precludes it. Doing that to yourself is illuminating; doing it to somebody else is just plain nasty. Besides, perfect things are transitory by nature. Held closed in memory or kept as principle, they turn rancid, however gently they are tended.

I haven’t done any more solos. Perhaps someday I will again, when I’m no longer wrapped up with other people or when I’ve honed my schizophrenia to an edge sharp enough to cleanly divide climbing from everything else. Until then, I’ll use a rope to protect me from falls and dangerous expectations.