There is an interesting post here about jargon. It explores one of the useful aspects of jargon, and as a consumer – indeed a purveyor – of jargon in the medical field, I completely agree. Technical terms give us simple clarity, and simple clarity is one of the most useful things around.

The post focuses on the utility of jargon within its natural environs – dialog between professionals, where it is quite useful as shorthand. As an example from my world, when I say ‘appendicitis’ to someone in the medical field, a fairly specific array of physiologic and anatomic processes comes to mind, along with their likely manifestations, consequences, implications for diagnostic testing and treatment, associated research studies, etc.

The conversation can move right along. Plus by way of its scope, the use of technical terms can serve as a check point in the dialog. If there is a malapropism, it is apparent.

When a colleague says, “The negative ultrasound ruled out appendicitis..”, the conversation must stop. We must clarify why he thinks that the ultrasound ruled out appendicitis, because it is commonly accepted that ultrasound does not, in and of itself, rule out appendicitis. The term ‘appendicitis’ as jargon, contains the understanding of its diagnostic criteria for those in the know.

The situation is different when a patient says, “I think I have appendicitis.”

Typically, the lay person who makes that statement knows little to nothing about appendicitis. The word refers to little if any of the content it carries when I mention it to a surgeon. However, the same process flows from its use, or rather misuse.

The lay person’s usage brings up the question, “Why do you think that you have appendicitis?”

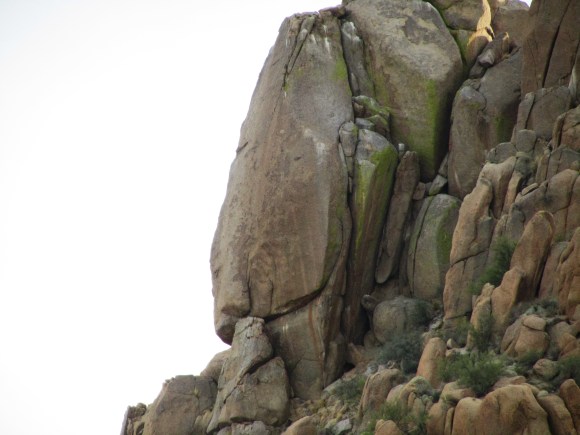

In other words, technical terms provide some solid surfaces in an otherwise squishy conversational world. If we can’t alight upon them, then at least we may bounce off of them in some direction, rather than landing splat in misunderstanding or mere conflict.

The common complaint that jargon is obfuscation doesn’t hold up when we consider the honest usage of technical terms, even outside of their professional environment. There is, however, a dishonest way of deploying jargon.

The current poster-child for such corrupted terminology is ‘mindfulness’. In its original sense, the word referred to a non-reflective state. The idea was: your mind stays fully engaged with what is happening in its scope of awareness, without reaction or abstraction. It was the kind of thing which dart players, test-takers and athletes sought.

Now, though it still gets used to mean engagement with the present, it may also stand for a state of detached self-awareness, in which one is monitoring and regulating one’s responses to one’s present situation. Clearly, the latter meaning is at odds with the former, if only because the latter refers to an essentially reflective activity. Dishonest users of the term shift back and forth between the meanings depending on the goals of the user’s discourse. If the occasion is a corporate retreat aimed at promoting harmony in the workplace, the second meaning is used. If the speaker wishes to convince the listener that chronic back pain does not require morphine if one simply ceases to reflect upon said pain, then the first meaning of mindfulness is implied.

Clearly, the sort of shenanigans at work when people bat around ‘mindfulness’ are what give jargon a bad name. Mindfulness started out its career innocently enough, as something which Zen practitioners and coaches discussed. But along the way, it picked something up. As something useful, it came to possess an air of desirability. As something desirable, it acquired the reputation of being something good, and then, of being good in itself.

Once imbued with moral character, the technical meaning of mindfulness, along with all associated contents relating to its use, became subsidiary. Being mindful became less important than being a mindful person, and when a moral role presents itself, it is open for definition. The corporate lecturer can tell us what a mindful person does at work. The pain specialist can tell us how a mindful patient takes medicine. The roles make the meaning henceforth.

The situation seems at least a minor victory for the moral expressivists – those who claim that our moral claims are not claims at all but expressions of sentiments like approval and disapproval. It would be a victory too, if the abusers of technical terms were actually making moral statements. But they are not.

When people utilize a bit of jargon with moral character, they are using it as a means to an end. They are weaponizing it. The listener doesn’t receive a sentimental expression from the speaker; the listener is invited to fill in the sentiment. The audience at the corporate retreat must make the connection: a weekly post on the suggestion board means I am mindful, which means I am good. That line of thinking isn’t really moral reasoning; it is a facilitated rationalization.

Jargon as a technical tool is not the problem. Yet, we are right to be wary of jargon. Its use should put us on the lookout for manipulation. But we should not be afraid to use it either. We must just take care to use it mindfully, by which I mean being critically aware of one’s attitude toward the current subject, which was once known as being an adult. Oops…