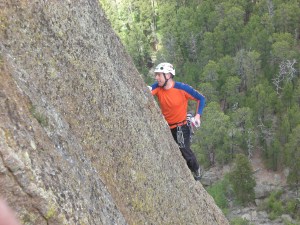

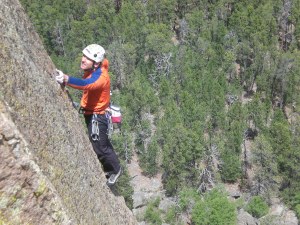

The Diamond is the upper half of the East Face of Long’s Peak in Rocky Mountain National Park. It gets its name from its shape, but the name also fits it from a climbing perspective. The vertical to overhanging plate of granite is striped with cracks from the width of a fingertip to the width of a basketball. It is a jewel, and irresistible even for sport climbers from Chicago like me and Jim were.

In our defense, we were not sport climbers by choice. Living in Chicago severely limits a person’s options. Despite our circumstances at the time, both myself and Jim, had extensive experience in the mountains, including long routes in the Tetons. Our experience meant that we were not complete fools to think we could climb the Diamond in the first place, but it also meant that we should have picked up on a few clues that things might be off track before the incident.

The line of evidence goes all the way back to the contemplation phase. When I was thinking about a big trip in those days, I always tried to run the idea by my friend Tim. He was a veteran of Ama Dablam and the Cassin Ridge on Denali as well as a living, intact paraglider pilot, so I figured he must know something about risk assessment. He was also a model pagan skeptic of Swedish heritage, born and bred in a factory town in upstate New York. He soft-pedaled nothing.

“What?” he said, “the Casualty Route?”

He shook his head. When I corrected his assumption that we intended to climb the Casual Route (the easiest and so most popular route on the Diamond) he dialed back the distaste a single click.

“Yeah, well,” he said, “the whole place is a god damned zoo. Good luck.”

I ruminated on his comments just exactly up to the moment I looked at the picture of the Diamond in the guidebook again. Then I forgot about them until the trip back from Colorado.

The scene at the registration office should have refreshed my memory sooner. It was climber Babel. There were kids and old people, dirtbags in flannel shirts with frayed ropes slung over tattered backpacks and teams of smartly dressed outdoorsmen lugging huge, spotless haul-bags. We got one of the last remaining permits to sleep in the boulderfield below Mills glacier at the base of the East face. When we arrived at the bivouac site, the sun was setting and the slopes, speckled with headlamps, looked like a reflection of the Denver suburbs far below.

The North Chimney was not the best approach to the Diamond, but it was expeditious and that was important in a race. As the first light of morning touched Long’s summit, the dash for positions on the ledge atop the lower East face was already well underway. Several of the wiser teams crept up the snow slope at the far edge of the glacier. Others descended ropes from the plateau on the other end of the precipice. One group had chosen to climb the shield of rock in the middle of the lower face, and daylight found them hauling a fully assembled portaledge up their route, the frame of the collapsible sleeping platform bumping along like a kite stuttering across the ground in a high wind. One group was ahead of us on their way to the chimney. Another trailed us by just a few minutes.

The North Chimney was not the best approach to the Diamond because it was not a climb and it was not a walk, it was a scramble – easy hand-and-foot climbing. As such it was easy for a climber to ascend without a rope – a little less so lugging a heavy pack and even less again wearing hiking boots. In other words, it was fast, loose and dangerous.

The party ahead of us was well out of sight and, we justifiably assumed, probably clear of the chimney when we started up. I was in the lead, about twenty feet above the gap between the top of the glacier and the base of the lower East face at the moment that they yelled, “Rock!”

On hearing that warning cry, a climber has two choices: look up in hopes of dodging the missile or hug the rock and rely on the strength of one’s helmet. I was in poor position to dodge, supported as I was by hands and feet on a steep bit of the scramble, but the ominous sound of what was coming convinced me that the helmet might not suffice. I did manage to head-shuck the first , cantalope-sized chunk, and ducked the next, slightly larger stone as it bounced over me. The third one wasn’t bouncing; it was too big. It grated along in light contact with the face, striking sparks. I leaned back to get out from under it.

As the block cleaned me off my stance I slipped into a certain clichéd state which I’ve only rarely experienced. Time slowed down. I felt myself tipping back, the heavy pack dragging my shoulders down faster than my hips. I felt my partner’s hand on the bottom of the pack and though it was physically impossible ( my helmet had been pushed down over my eyes and the broken edge forced through the end of my nose by the impact) I saw him trying to keep me from flipping over. I couldn’t right myself. I didn’t have enough leverage against his outstretched arm. However, the force was just enough to let me twist and face out from the wall, reversing the pull of the pack. My new position felt better, but looked worse. From beneath the broken rim of my helmet, I saw the long sweep of glacier below, lying at the angle of a ski run and now strewn with debris. At the top of the slide was a black moat between the rock face and the ice. A narrow ledge projected into the shadow a few feet below the lip of the ice. I aimed my heels at the ledge and put my forearms out in front or me.

The impact must have hurt, but I have no recollection of it. I might as well have settled like a feather balanced on the edge of the ice. Immediately, I was fumbling around in real-time again, trying to pull the pack over my neck as the tail end of the rockfall pummelled my back and legs.

I’ve often wondered what was going on in those first moments. How could I have a memory of seeing my friend spotting me when I couldn’t possibly have seen him? How could I make decisions in the span of time I had to react? I think the Hagakure may hold the answer.

“Even if one’s head were to be cut off, he should be able to do one more action with certainty.”

Quite an odd notion on the face of it. The idea is sound, though. Newborns show a visual preference for faces at nine minutes of age, and this too is an odd notion. We have inborn comparators against which our identity is a reference point and we refine and build on those comparators as we grow. That constant process comparing current state versus prior state versus anticipated state is the root of consciousness itself. Pre-reflective consciousness, our direct, subjective experience, is not pure perception. It is beautifully impure. The mind maps the present onto the past and future by the moment. It is only in moments of utmost need that we lay down enough memory to see the process at work. So the mind, if it has the right set of references at the fore, might seem to carry out one more anticipatory action, in death or in life, such as putting out a hand as if to spot a partner’s fall.

What good is this understanding? Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s most beautiful thought answers:

“There is surely nothing other than the single purpose of the present moment. A man’s whole life is a succession of moment after moment. There will be nothing else to do and nothing else to pursue. Live being true to the single purpose of the moment.”

Sadly, we cannot escape reflection and live the dream the author sketches in this passage. We have to face the horror of war that comes with the joy of battle. However, we can hope to keep the two straight, the reflective and the pre-reflective, and that is what understanding is good for – holding onto memories without bending them into trinkets or icons.

That’s what I walked away with from the base of Long’s Peak, having been smashed in the face by a large rock. That, and the knowledge that the Diamond is indeed a god damned zoo at the end of August. And the realization that I should pay more attention to Tim’s opinions. And four tiny, blue, Kevlar threads lodged in the end of my nose.