It can’t do anything on its own. But give it just a little bit to go on, and it will make your damn world reliable.

Dedicated to the Game

Climbing and other disturbing things.

Tag Archives: truth

“They Are Under My Skin”

I look at the small red spot on his arm and then at his eyes. My heart sinks. The red spot appears to be an irritated hair follicle. His gaze is steady and forthright. I am the 3rd doctor that he has been to for this problem. I recognize the diagnosis. I have seen many people over the years with his same complaints. I have treated many people with those complaints for lice, scabies, and other parasites, with great success. However, I have never successfully treated the condition from which this person suffers. Though they have symptoms which occur with a parasitic infestation the patient is actually afflicted by the belief that they are infested. They harbor a delusion.

A delusion is a fixed, false belief. In many cases this definition is not controversial. For instance, if someone believes that the CIA is controlling their thoughts and actions by means of a radio receiver implanted in their brain, we can quickly conclude that such a thing is demonstrably impossible. It doesn’t fit with what we know about structure of the brain. Such a receiver should be detectable by electronic means or by imaging. It is difficult to imagine how the device might have been surreptitiously inserted into the victim’s head. In other words, none of the stories that we could tell about the mind control device can be squared with any of our well-worn stories about the rest of the world. The glaring falsity makes the fixation easy to expose. When the delusional person suggests that the implantation was accomplished via a trans-sphenoidal incision which would leave no obvious scar, and that the receiver is made of material which nonmagnetic and radiolucent, and that the whole system operates on burst transmissions which are only detectable with cutting edge equipment which is currently only available to the CIA, it is pretty obvious that they are merely doing whatever it takes to preserve their belief rather than proposing a serious explanation.

The trouble is: the method we use to reject the mind control device story is not anything special. We compare experience – our own personal experience as well as our collective experience – with the contents of the mind control device proposition. If things match up, we believe the claim. If the pieces of a mind control device do not fit in to the puzzle of our world, we are prone to say that the claim is not true. The comparison process is not precise though. We often don’t have experience of every aspect of a claim. We also have questionable access to claims, especially when they relate to other people’s experiences.

We may tell people that we feel their pain, but we can never mean it literally. Herein lies a delusion’s opportunity. A dermatologist can tell you that they find no evidence of scabies mites, lice, or plastic filaments erupting from your skin. They cannot tell you that you are not itching in just the way and in just the places that people with scabies report itching. When confronted with such observations, the dermatologist must admit their ignorance., or face the same incredulity with which we greet the story about the mind control device. Furthermore, if the dermatologist is ignorant on that account and yet willing to forge ahead with a diagnosis, what are the limits of the doctor’s hubris? What other evidence has the smug twit disregarded?

The question used to be mostly rhetorical. It was part of that argument from incredulity. Now, the question has a ready answer: all that stuff on the Internet. There is a case report to support almost anything imaginable. Plus, there are instructions on how to investigate your own case. It is quite clear, once a person has it under the oil immersion lens on their home microscope, that the speck they picked off their forearm is not a skin flake, it is a bug. And by the way, patients cannot help but notice the lack of such equipment in the clinics which they visit in pursuit of the truth regarding their signs and symptoms.

Those who imagine that they have parasites, no longer need rely on the necessary limits of our knowledge as they contend with the medical establishment. The volume of unsorted information available to them dilutes any counterclaims. In the process, reams of reference material hide fixation. All the delusional person rejects are the hasty diagnoses of a few arrogant physicians. Those physicians are rejecting a body of literature which exceeds the memory capacity of the patient’s cell phone.

I have never successfully dispelled someone’s delusion of parasitosis, but I have come close, maybe even close enough. The patient had come to me with the usual complaints: rashes and bumps on her skin, itching, crawling sensations. She brought in the usual box of samples and sheets of lab tests. I had failed the 2 previous people who I diagnosed with this delusion. One of them simply never returned after I told him that we had done all the testing that we could and, though I could not tell him why he was having his symptoms, I could at least reassure him that the symptoms were not due to a parasitic infection. The other one walked out in the middle of their last visit after I told them that they ought to consider an antipsychotic for their symptoms.

Previous cases fell apart just about the time of diagnosis. This time, I resolved not to conclude no matter what. We looked at the samples. They were like Rorschach blots. Suggestive shapes faded in and out with focal adjustment if you were prepared to see them. All the labs were normal. There were no significant findings on previous skin biopsies and attempts at sampling from skin lesions were consistently negative. But her labs were consistently normal over time. She was feeling well. Her weight was stable. She did not have any allergy symptoms. Whatever might be crawling on her making her itch did not appear to be doing her any serious harm. Maybe this organism was more like all the mites and microbes peacefully inhabiting the backwaters of our anatomy, than it was like the bloodsucking arthropods that sometimes attack us. It was a successful detente for all of us

All that stood between us and level ground was the truth. It needed to be teased free of all the suppositions woven in with it, almost down to the facts. What remained when the sorting was done was a series of flat statements (I itch, there is a bump on my skin, I feel like something is crawling on me) without distorting references to a justifying theory. She no longer started with bugs under her skin as the primary description of her problem, however compelling the image.. She began with the itching and crawling sensations. The sensations meant what they meant without entailing the massive tangle of hypotheticals and contingencies that accompanied the bugs.

I was also forced to pick apart truth and supposition in my thoughts on her complaints.. Diagnosing her generated a fixation of my own, because it committed me to considering a single aspect of those complaints. To be honest, when I could find no insects, I immediately began to see her as deranged, and so I set about correcting her derangement without a 2nd thought. But my perseveration on the pathological nature of her delusion just fed its gravity.

We all suffer from delusions from time to time. Almost everyone is subject to a “mild positive delusion”. That entity is simply the fixed, false belief that one is more capable than they actually are in any given situation. At first glance, the mild positive delusion appears to be just a fancy name for foolishness. But it is hard to see how anyone would ever get better at anything without it. The delusion pulls a person into situations slightly beyond their control. That zone between comfortable mastery and havoc, is where learning occurs. Of course, not all delusions are so benign. Delusional beliefs may generate heavy, dark hypotheses which draw the deluded to grim actions.

The prime example of such a delusional black hole would be the shooting incident in a small pizza restaurant which occurred a couple years ago. The shooter disliked certain politicians. He took note of some stories on the Internet which tracked well with his estimation of those politicians character. He then began to actively search for such narratives. This drew him in to the point that he became absolutely convinced that the distasteful politicians were a cabal of child sex traffickers operating out of a small pizza restaurant on the East Coast. He subsequently packed his rifle in the car and drove to the pizza joint, where he demanded the release of the imprisoned children and immediate apprehension of the evil politicians. He fired a few shots in the air to emphasize the seriousness of his conviction.

For good or ill, we will never be free of delusions. We cannot do without them. Rather than undertaking the extermination of fixed, false beliefs, we might instead try to limit the pull of their gravity, as my one successful patient demonstrated. That means taking care not to mistake the theoretical structures which delusions generate for the truths undergirding the delusions. That way, when we find ourselves standing in the middle of a pizza restaurant with a rifle, we understand that we are standing in the middle of a pizza restaurant with a rifle. And we itch if and only if we itch. That much would be true.

Revelations

In terms of what we know and how we know it, we are really no better off than scorpions, who are guided by shadows, cthonic vibrations and the fading scents of long gone passersby. For example, if I have a headache, I take some ibuprofen. I believe it will help me because I know how it works. I learned about the mechanism of action in my chemistry classes, and in subsequent review of the medical literature. But I have never seen the chemical do what those sources say it does. Nobody has seen ibuprofen at work, because the molecules are too small, and the reactions are too fast. However, there are ways to magnify the actions of the chemicals in question, so that those actions may be observed indirectly.

I have not even done that. I have read papers and listened to people who explained how they carried out those observations. Having compared their methods to the methods which I learned in chemistry classes and validated in the lab, I believed their report.

Therefore, I take the pills from the bottle labeled ibuprofen when I have a headache, and expect relief. As I choke down the maroon tablets, I act on a belief even more flimsy than the notion that ibuprofen will help my headache in the first place. I have no idea how the pills were made, and no way to know whether they contain ibuprofen at all. Within an hour, my headache is better.

I keep taking ibuprofen from those types of bottles, because it keeps making my headache go away. Maybe someday, I will unknowingly take a cyanide tablet instead. The risk is negligible though. The same biochemists, pharmacists, and physicians who taught my classes, and subsequently formed my beliefs about ibuprofen’s effect on pain, have declared their commitment to assuring the integrity of those maroon tablets in the bottle labeled ibuprofen on the drugstore shelf. The company that makes those pills has also committed to the recommendations of the biochemists, pharmacists, and physicians regarding the purity of the pills, and the company charges a price which reflects its commitment to giving me ibuprofen, the listed dose of ibuprofen, and nothing but ibuprofen in the bottle.

Philosophers have contended that knowledge is justified, true belief. It turns out though, that truth is probably too small for that purpose. Yet even without truth as a necessary condition, we know something. We go to sleep without fear of never waking again. We take one step after the other confidently, apparently certain of the ground’s persistent solidity. We move about justified by an interlocking network of constant correlations. Any single one of those correlations may be dubious, but taken as a consistent whole they support actionable beliefs – knowledge.

Like the scorpions’, our basics seem pretty janky. Nevertheless, though we are occasionally crushed by a boot or have to sting our way out of a situation, we survive for the most part, and even manage to snag an invigorating insect or two along the way.

It is possible to doubt a functional view of knowledge however. Anything less than absolute certainty merits some doubt. I think about that stray cyanide tablet now and again. Yet, I don’t doubt the justifying power of consistency built of constancy. I know that my pills are ibuprofen even though they might, in principle, be cyanide. Doubt in the method of justification itself invites fear, and fear is contagious.

Such doubt in our body of knowledge, driven by attendant fear, has spread in the populace recently. In place of functional knowledge – beliefs justified by their ties to a massive network of constant correlations – the afflicted strive to reclaim truth as their foundation for knowledge. They cast about the culture for a suitable candidate, what they find is revealed truth. Revealed truth has always lurked about in the cultural murk. Religion harbors it, but not the superstitious type of religion which one might reflexively suspect of such activities. The God of the Old Testament felt the need to carve a tablet, burn a bush, and drop some manna now and again. Revealed truth instead finds refuge with the more philosophical types. Think divine command theory or moral intuitionism.

Revealed truth acts something like Platonic form. Taken as a form, a circle is not a good model, it is the underlying reality which the flawed material of our world imperfectly represents. The circle itself is not the stuff of experience. Revealed truths differ from forms on that point, though. Revealed truths can be apprehended, and so blur the line between analytic and synthetic truths. The statement, “all unmarried men are bachelors”, is an analytic truth. The statement, “Bob is a bachelor”, is a synthetic truth. The statement, “Bob is an inherently unlovable person” is a revealed truth. On the same basis, what the Bible says is true because God wrote the Bible, which we know because it says so in the Bible. It is a truth by definition, but only in reference to a given assertion, in this case that an infallible God is the Bible’s author.

With revealed truth in hand, a person can know something with absolute certainty again. The result is appealing. We needn’t waste our time on the uncomfortable task of finding a date for Bob. We know what he is now.The problem with revealed truths should be obvious at this point. Such givens undercut justification. Consistency with the constancies does not matter anymore, only consistency with the given. If Bob actually gets married, we already know that the marriage is a sham. What remains is to discover the structure of the sham.

The justifying structures are easily built, and unassailable, since they have a given between themselves and any assault. The givens themselves are not beliefs, but natural conditions or kinds revealed by an authority, whether it be an intuition or the speech of a erstwhile prophet. Pick your definitive source; there are no limits.

This spoiled conception of knowledge has spread, generating Q anons, Antifas, and vaccine microchips. Similar epidemics have washed over us in the past. They never last, because eventually, the pragmatic view of knowledge outlasts them. Knowing the spells tucked in their jackets will protect them from bullets, a few of the participants in the Boxer Rebellion manage to avoid being shot. Most die. The scorpion who knows that he can wander around in the daytime because he feels the protective hand of God upon him will survive, for a while. The patient on the ventilator may know that Covid is a hoax because evil people lie, and evil people told him about Covid. He will still drown.

The Other Senses

We humans have a visual bias. Experiments have demonstrated our preference for sight, but there is no need for experiments. “The proof of the pudding is in the eating,” not the tasting, but “Seeing is believing,” they say. Whenever we want to illustrate something, well, we illustrate it. Our language and culture reify vision. Even our metaphysical discussions are rife with visual references: consider Mary the color scientist, spectrum inversions, and Gettier problems.

Our belief in seeing privileges our sense of sight relative to our other senses, and we are likely to take its instruction more seriously. We wave off any perceptual conundrums arising from our other senses as foibles of inferior organs. But we should take our nonvisual phenomena more seriously, for they have lessons for us if we do.

Those lessons start at the bottom, with our sense of smell. Though it is our crudest sense, and arguably the one sensory modality that we could most do without, the structure of smell has weighty implications. Olfactory neurons each bear a single kind of receptor. The odors we experience are mediated by activation of a set of receptors entirely. The number and distribution of that activation determines everything about a smell: its intensity, favorability, and motivational power. An odor is something which can be described, but not named. There is no equivalent to “red” in our odor palette. However, there are good and bad smells, and as with moral qualities (supposedly), smells are intrinsically motivating on the basis of their goodness and badness.

That motivational power lies in the smell itself. A chemical in a test tube which smells like a steaming pile, produces the same revulsion as the smell of a steaming pile itself. It is tempting to say that the odor of the chemical in the test tube is just an olfactory misrepresentation of crap. The common scent is supposed to smell just as it does, though. The smell is a conjunction linking an aversive mood, and things to be avoided. The smell and the mood are about a broad landscape, stretching over memory, history coded in our genetics and cultural instruction, all mediated by a particular pattern of receptor activation.

A similar sort of two-directional representation occurs in our auditory experience. The organ which generates auditory nerve signals, the cochlea, is tuned to the range of the human voice. The structures at the auditory end of the line are primed to respond directly to voices and music, and indirectly, to stimulate an emotional response to voices and music. As with smell, when hearing evokes a mood, it builds a memory of itself and its circumstances on a broad and sturdy base. A good framework improves the recollection’s relevance, and therefore its odds of survival. Here is another temptation. Fans of evolutionary psychology and divine teleology may see the beginnings of a good story in this structure. But those sorts of stories are unnecessary, and far beyond the point, which is: our hearing shapes the map of our experience in terms of words and music, as much as it recognizes musical and linguistic experiences.

The other senses break down the uni-directionality of representation, but even further, they blur the internal/external division itself. Taste receptors give us the sensations of sweet, salt, sour, bitter, and umami. Our conscious experience of taste locates those sensations on the tongue. But there are taste receptors for bitter and sweet in the pharynx, and sweet taste receptors throughout the intestinal tract. Those sweet receptors attach to neurons which do not reside in the central nervous system, but instead, lie in the intestinal tract itself, and the pancreas. Though these sense organs have no direct connections to the central nervous system, they still contribute to conscious experience. They simply do so via the adjacent somatosensory system.

Our somatic senses are a bit of a jumble. As a whole, they are the thing that represents our status. Though there are a few specialized sense organs in the system, it mostly relies on bare nerve endings and chemical signals built in to the tissues surrounding the nerve endings. This sense tells us where our limbs are, and what each appendage is doing. The somatosensory system lets us know when our gallbladder is on the fritz, and, indirectly, when we are hungry or full..

Though they are rarely the center of our conscious attention, our somatosensory experiences are always present in our conscious states. If I interrupt Dr. Penrose’s visualization of a 5 dimensional object, he will immediately be able to tell me whether he is standing or sitting, feeling hungry, feeling warm or cold, fit or tired. Somatosensory experience serves as the shade tree, grass, and sky in the painting of our phenomenal picnic.

Of all the senses, our somatic sense most effectively dissolves the boundary between what is internal and what is external. Because, our hunger is apparently our hunger. Our cold is our cold. These are things that seem to incorrigibly belong to us, just like our thoughts or our moods.

The thought that any of these things belong to us is a bit off anyway. Words and music, hunger, thought, and mood are constituents, but there is no separable “us” to which they may belong. We come by this error regarding identity via our most favored sense. Because we rely so heavily on vision, we confer an unmerited degree of independence to our visual experiences. We conceive of sight as purely received information, which given the limitations of the medium, naïvely represents an unconditioned reality. The plain truth gets transmitted through our optic nerves, into the dark room behind our eyes for the viewing pleasure of a little man in front of his little screen – the real us. Visual realism leads to other mistakes in its turn, regarding what is real and what is not. We begin to believe that numbers may be real because our eyes see objects as very discrete. Geometric shapes may seem real because we are able to depict them visually. A separate observer made up a separate stuff must sit behind our eyes to validate the reality of our visions. Our other senses beg to differ. They give as good as they get. Their contributions to our experience only make sense in reference to our global experience itself and do not rest on some outer, hard surface. Our world may be a ship sustained by the tension of its own spars, but it works for us – better than a brittle realism would.

Causes, Facts, and Heroin

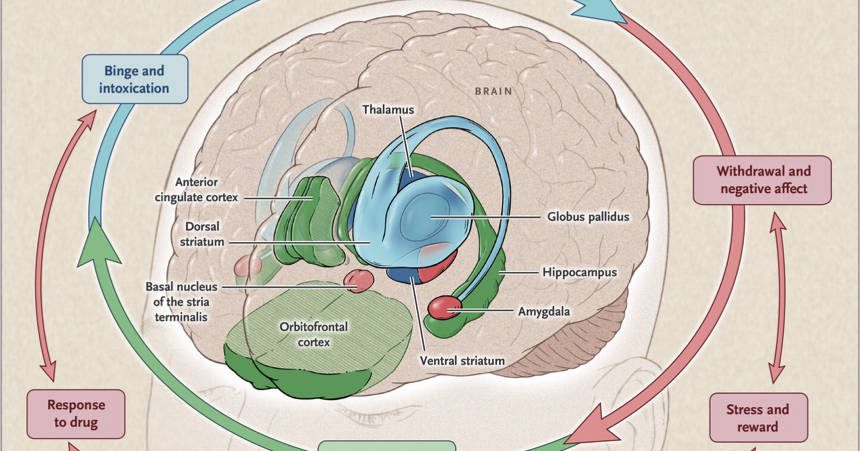

The lecturer moved his laser-pointer quickly over the loop of neural circuitry. He explained the role of Mu receptors in activating the circuit, which sent a signal round and round and came out as the behavior pattern we call addiction. It was all very neat.

It was so neat the he could have simplified his diagram by replacing the pretty brain graphic with a switch. Off would be synonymous with no addictive behavior. On would equal addictive behavior. If you took the theory, “Addiction = Brain Circuitry” at face value, anything that flips the switch would cause addiction. Yet we know that that situation does not obtain. Heroin flips the switch, but not everyone who takes heroin manifests addictive behavior.

For the advocate of “Addiction = Brain Circuitry”, there are two ways out of this dilemma. First, he can posit a multiplicity of switches. In other words, he can claim that there is an intervening network of necessary, but not sufficient, switches on either side of the Big Switch, mediating the input and output of the addiction circuit. But then in principle, all those switches could also be replaced with a single switch, and you are right back where you started. No limited set of if/then statements will be completely determinative.

The second way out of the non-correspondence dilemma is to simply abandon a complete and transparent explanation, in favor of reliable facts. Neurons are necessary to behaviors, and we know that because, if we zap certain neurons, we can reliably alter corresponding behaviors. That doesn’t exactly explain the behavior, but it lets us move on to knowledge of neural circuits and the experiences which correspond with changing the configurations of those circuits.

One might denigrate the second solution as an abandonment of truth-seeking. Perhaps, but that is not so bad, on a proper notion of truth. In solution #2, you get a theory, which is a set of reliable facts. To get to the truth what you need is an explanatory reduction. In other words, all the switches and their positions for a specific moment of behavior, across the cosmic board. Such an array is purely didactic. It refers to no knowledge, for it cannot reliably correspond with anything. You may think you know something about it, but you don’t – not until you begin to formulate a theory regarding it.

Johnnie shoots a dose of heroin because he has inherited a susceptible set of receptors, because he contains the dendritic representations of certain permissive life-lessons, because he lacks certain inhibitory representations, because he lives in a society which has heroin, because he anticipates certain effects from heroin injections. And on, and on, and on…

At the end of such an exposition (if there even is an end) what we have is just a snap-shot which we have pre-labeled, “Johnnie’s Addiction”. To make any sense of it – to know anything at all about it – we must delve in to the insufficient necessities, and be satisfied with their mere reliability. When we give Johnnie a medicine for his Addiction, we should expect that it will, to some extent, extinguish the behavior. We should expect that if we take away his heroin, his behavior will, to some extent, change. And in fact, our theory does correspond with the facts which it predicts, and upon which rests.

Like the addiction lecturer, we all frequently feel dissatisfied with reliability. We would like some non-provisional knowledge. Give us some truth, please. Aspiring to truth gets us nowhere, though. Truth is too hefty. To riff on Gettier’s classic thought experiment, Smith has the truth when he observes that a person with 10 coins in his pocket will get the job, once Smith sees that a person with 10 coins in his pocket gets the job. Yet he has no knowledge thereby. He cannot be (provisionally) right or wrong in such a statement, any more than a snapshot can be right or wrong (though our subsequent interpretations – theories – of the snapshot may be).

If Smith says, at his next interview, that the person with 10 coins in his pocket will get the job, and he takes care to put 10 coins in his own pocket in hopes of getting the job, then he may know something. He is making a knowledge claim regarding his experience with coins and interviews, and his claim may or may not correspond with his theory’s fact-conditions. Reliability is what he will get, and he will be happy with it, or not, as will we all.

What Did You Expect?

Did you expect that professional intelligence officers would involve a bunch of loud-mouthed incompetents in their operation?

Did you expect any persuasive evidence to come from an investigation for a population which, as Trump accurately estimated, would not change its vote if its candidate shot someone on 5th avenue?

Did you really need a conspiracy theory to convince you that the author of the Mexican rapist invasion, fine folks in the Neo-Nazi (Alt-right) ranks, Enemy of the People press, dictator admiration and non-stop smack/lies needed to be evicted from office and reviled in the histories?

Really?

Balance Impaired

Close-up, the little gully evoked a strong sense of deja vu. The angle suggested that one might almost be able to stand up and walk it. The rock looked like a crocodile’s skin – all knobs and chunks with few cracks or pockets – and the few voids in the surface had formed from the erosion of yellow clay inclusions. I had been in this situation before, in the Canadian Rockies, the Tetons, the Cascades. It meant sparse and dubious protection for insecure climbing, with an ugly fall looming throughout.

Close-up, the little gully evoked a strong sense of deja vu. The angle suggested that one might almost be able to stand up and walk it. The rock looked like a crocodile’s skin – all knobs and chunks with few cracks or pockets – and the few voids in the surface had formed from the erosion of yellow clay inclusions. I had been in this situation before, in the Canadian Rockies, the Tetons, the Cascades. It meant sparse and dubious protection for insecure climbing, with an ugly fall looming throughout.

The fresh memory of yesterday’s Eureka foray reinforced my unease. Just going into the mining country in Colorado’s San Juan mountains is sobering. The road winds through acres of avalanche terrain peppered with jumbles of gray boards and rusty iron marking the eternal resting places of generations of abandoned avarice. Eureka itself stands for self-consciousness of our bitter relationship with the range. Once a small, hopeful mining community the town is now a single building. The lone, windowless watchtower bears a prominent sign with the name of the town, placed there, no doubt, by the same sort of joker who might strap a party hat on a skeleton.

Yesterday was our second consecutive day at the ice climbs in the valley above the ghost town. The day before, we had been denied access to the longest climb in the area by an SAR exercise. Yesterday, we encountered a line of four parties on the same route, and we decided to trudge a bit further past the routes at the valley’s entrance. Around the bend and not far above, we found a lovely pillar of ice baking in the sun. The air temperature was cold however, and the ice looked to be in good shape from the ground, so we went for it.

My partner took the lead and ran the two pitches together. It went well until the very top. There he found the last few feet melted out and he could not get to the fixed anchor. Worse, in a fit of hubris, neither of us had thought to have him take the kit for building ice anchors. He put in two ice screws at his high point and I lowered him back to an intermediate ledge. He set up a belay and I set off to retrieve the ice screws and build an anchor in the ice to get us back down to the base.

Looking up at the situation, I knew that I should not risk falling. He had placed the two screws at the anchor properly. They had already held his weight on the lower. But the stainless steel tubes were basking. Many times, I had raced the process now at work on the anchor, placing another screw on a sunny climb before the last one heated up enough to melt loose. I arrived at the anchor and placed a back-up screw. Out of curiosity, I jiggled the anchor screws. They rattled in their holes, and by the time finished the rappel anchor, I could lift the screws free with two fingers.

By the time we got back down, the crowds had migrated our way. We had another objective in mind for the afternoon, but our hopes were squashed on the road, for we found a fellow standing at the head of the approach trail just staring across the valley as if he were reconsidering something. He informed us that he had ridden a slab avalanche for a few meters down the slope below our goal. My partner had his wife and young son waiting back in Ouray anyhow.

There had been angst around bringing the child, who was their first. He was a nidus of concern in some familiar ways. He was 18 months old and did not want to eat or sleep regularly. He clearly understood everything said to him, but his only bit of expressive language was the word “No”. Each morning, he spent a non-stop hour on Rube-Goldberg action. Cups went into other cups, packets of jelly were transferred from person to person and then into the cups, and then back to their original owner. All of this chaos worried his parents. It seemed so overwhelming that one could hardly imagine any organized behavior arising from it.

Unless you had seen it before. I had. I distinctly recalled worrying about how I could possibly teach my first child to speak. I had no training, and no idea where to begin. Nevertheless, the kid started to talk. He had inherited the talent for it. From an adult perspective, it looked like a miracle, because adults liked to think that they had, each and every one, invented the world – or at worst discovered it. That way, the adult felt more competent, and the world seemed more solid.

From the child’s standpoint, he was building a constellation from the inside out. He had his experiences – what he might come to call ‘sense impressions’ should he grow into a particularly deluded adult – and he had the dots and lines to mark and tie together those experiences, inherited in his nucleic acids, language, and culture. The dots and lines were powerful tools. They would allow him to develop at heady pace, mapping out massive territories, like language, on the fly.

His ancestral mechanisms assembled his star chart in a blur, and if he was at all self-conscious in his adulthood, he would spend a lot of time figuring out how he got there, and what kind of picture he had made with all those dots and lines overlying the bright spots of his experience. It would be daunting and he might be tempted to throw his hands up and just call the dots and lines the truth, to give the mathematical, linguistic and philosophical accretions on experience an undeserved solidity, while relegating the experience itself to a dirtier, incomplete status.

My partner’s son would have an antidote in that case. He would learn to climb, and that would at least open the blinds on the relationship between the picture of the stars and the stars themselves. He would still have to look, but most people didn’t even get that chance.

Perched in the little gully, I saw the true landscape.

I was not motivated. I felt the burden of all those extraneous considerations which populated the slope with angels and demons instead of little edges and blotches of ice. I climbed back down and handed the sharp end over to my partner. He was motivated, and managed to lead the pitch despite some misgivings about the security of the climbing. I followed without slips or fumbles. It was sketchy, no question. We looked at the next pitch, but decided against it. It would be there when the stars aligned favorably, or even better, when no one was thinking about the pattern of stars at their back.

The One Brute Fact

Even naming a brute fact, a Brute Fact, is the beginning of a mistake, but it can’t be helped.

Before I open my eyes, I am groping toward a mood. Some say that my mood will be nonintentional – that it will not be about something.

I disagree.

My mood will not have content, but it will stand in relation to something, in this case my unawareness at first, and then my time and place, and then where I left off before sleep. This ‘standing in relation’ – orientation in it’s most basic sense – is everything.

It is the bone of intention – the ‘aboutness’ itself, rather than the analysis of an intentional relation. It comes with consciousness and is not really distinguishable from consciousness. Logic (and its mathematical adjunct) models it, by permission.

Immediately, it yields identity and explanatory reduction. Further out, it leads to categories and theories. All this is natural to us, and renders meaningless terms like ‘supernatural’ and ‘separate mental substance’.

Curse You Peter Higgs

“Mass was so simple before you. Mass was just a property. Actually it was just a property of having another property: inertia. Inertia was so simple, though. It was just the property of resisting changes in motion.

Of course, we all know what ‘resisting’ means. And, we all know what motion is: d/t. If anyone must ask what distance and time are…well, there is little hope for someone so dim. At least, there is little hope for such a dimwit in physics. Hah! It looks like someone needs a metaphysician!”

The line of thought is a big hit with dualists. Actually, it is the best thing about mind/body dualism, and is why it’s good to have mind/body dualists around. Without them, physicalism grows too complacent.

The physicalist can be forgiven. It seems so obvious what we mean when we say that something is physical. But what does that mean? Is it simply anything that’s the proper business of physics? Is physics itself the proper business of physics?

The question of what makes something physical is actually difficult, even within physics. Take the Higgs field. It is not a ‘thing’; it is not even a ‘property’ of a ‘thing’. It is a property of space. It is a phenomenon which physics considers, but it is really weird, from the perspective of the old extended/unextended divide which Descartes proposed.

Yet we are prepared to accept the Higgs field as something physical, along with apples and atoms. That’s because we have been prepared to accept the physicality of the Higgs field by accepting the physicality of things like d and t in the Newtonian scheme, as physical. Time and distance are not any less weird – they are strangely malleable, for instance – but they are more easily recognizable as our own phenomena. We experience time and distance, and we are comfortable with the idea that physics is a phenomenology of time and distance.

If we have drilled down to the notion of physics as phenomenology, and understand phenomena as our experience, then the remaining question is: What is our experience? I am not sure there is an all-encompassing answer to that question. Yet I think we can say a few things around the question which are instructive as to the notion of physicality.

At base, our experience is identity, and identity is interdependence. If I am watching an egg roll off the counter and hit the floor, I am the one watching that egg. The rolling egg, among other things, is making me, me. The memories of eggs, dependent upon the shape, color, texture and historical context of my current experience, shape my thoughts and expectations regarding the egg, just as the color, shape and texture of the egg depend upon the impression that the kitchen light delivers to my eyes after it bounces off the rolling egg. That is what the notion of supervenience is getting at: identity is fixed by spatial and temporal history.

And such a thing cannot be ‘transcendent’. It comes with the here and now; (physical) existence has a tense. ‘Tenseless’ existence is a product of reflection and not what we directly experience. Transcendence, in other words, occurs in the storybook, not in the story (else we would never read a story twice).

The trouble with this whole picture is that it looks like a truism. If physicality consists of an interdependent identity which avoids transcendence, then what is left? Ghosts are live possibilities; so are Higgs fields. Of course, that is the point of physicalism. When we look at our experience in total, physicality seems to exhaust all the explanatory possibilities, or at least the ones we could hope to know.